A BIG QUESTION

To people in the ancient world, Jesus died simply because he was a troublemaker and a bad Jew (a glutton and a drunkard – Luke 7.34). For Jews his death was a stumbling block to any attempt to take him seriously; to Gentiles his death was foolishness. (1 Corinthians 1.23)

Of course, to those who had turned their lives around so they now lived with Jesus as their focus and their hope, his death and resurrection were a demonstration of ‘the power of God and the wisdom of God.’ (1 Corinthians 1.24)

That raised another question: if Jesus was the Messiah what did his death mean? The letters from various apostles in the New Testament promote a variety of ideas. Here are a few:

- a demonstration of God’s love (Romans 5.8);

- reconciliation with God (Romans 5.10);

- justification – being set right with God and declared righteous (Romans 5.9);

- an atonement sacrifice (Romans 3.25);

- being bought back/redeemed (Romans 3.24);

- carrying our sins and healing (1 Peter 2.24);

- dying for our sins to bring us to God (1 Peter 3.18); etc.

CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY

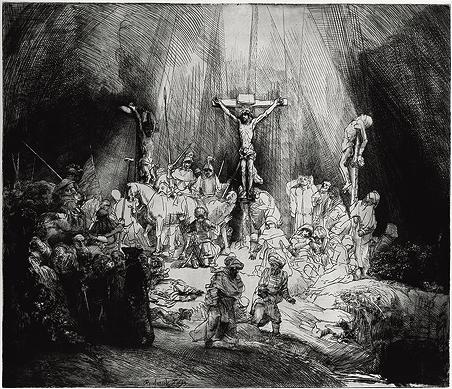

Over the last two thousand years there have been three main theories on what was happening in Christ’s death on the cross.

The earliest and most long-running theory, covering the first thousand years of Christianity, was that it was a victory over the devil and the powers of evil. The typical representation was that of a strong man on the cross, his arms held out horizontally, a strong young warrior. The imagery of the Anglo-Saxon poem, ‘the Dream of the Rood (or Cross)’ shows this:

This young man—

it was god all-surpassing —

strong and set in purpose.

He mounted upwards on gallows,

heightened & humiliated…

About 1100 AD two other theories were created. Anselm, the scholar-saint and Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote the influential book, ‘Why did God become Man?’ (‘Cur Deus homo?’). He argued that human sin and rebellion had caused an infinite loss in God’s proper authority and honour, and only a perfect man who was also God could bridge the divide and reconcile man and God. In the Reformation this theory hardened into the theory of penal substitution, in which Jesus took on himself the punishment for all the sins of humankind. This is still a key doctrine for evangelical churches worldwide.

Around the same time, the French scholar Abelard said that the cross showed God coming alongside the suffering and sin of humanity: “Jesus died as the demonstration of God’s love.” It is an appeal to bring about change in the hearts and minds of sinners. This idea of the cross as a moral example became a major approach in the 18th century. It is held by Christians who believe in a non-interventionist God, it is enough that we are God’s hands and feet in this world.

What did Jesus think?

BODY AND BLOOD

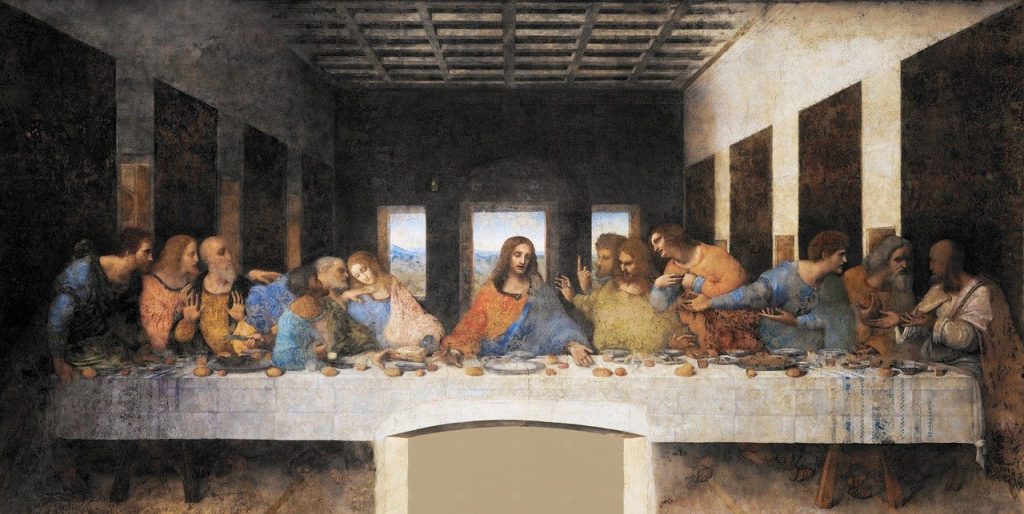

My father was an agnostic Jew. Whenever he visited us he would come to our Sunday service, always a Communion service. On one occasion he said to me afterwards that he found the service disquieting. To talk about eating the body of Christ and drinking his blood sounded to him very much like cannibalism.

It got me thinking. What would the twelve disciples have made of these extraordinary words? What context was there that would have made it possible to make some sense of them? I concluded that the only setting in Jerusalem in 33 AD which would speak of something other than cannibalism was the temple sacrifices. Earlier that day two of Jesus’ disciples probably went to the Temple, bought a lamb for Passover, had it sacrificed by a priest and skinned, then brought it to the Upper City where they could roast it on a spit for the next five hours. Jesus must have been indicating that his death was near, and that his death would be a sacrifice.

But what kind of sacrifice?

WHAT DID JESUS ACTUALLY SAY?

When I was writing my historical novel ‘Jesus the Troublemaker’, I had to pay close attention to just what Jesus did and didn’t say. The fact that he used bread and wine for his followers to remember him is indisputable. Mark, Luke and 1 Corinthians recount it in almost identical terms. My contention is that if we look carefully at the words we can discern what Jesus himself thought was the meaning of his approaching death.

Here are the reported words of Jesus:

During supper, Jesus gave out bread saying “Take it; this is my body.” (Mark 14.22, Matthew 26.26). Luke and Paul add: “which is (given) for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” (Luke 22.19, 1 Corinthians 11.24)

It sounds as if Jesus is simply announcing his forthcoming death. And giving his disciples a way to remember him, whenever they share a meal together.

Then Jesus sends a cup of wine around. When all have had a drink, he says, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.” (Mark 14.24); or “the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you.” (Luke 22.20) Paul ’s tradition has “the new covenant in my blood; do this whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me.” (1 Corinthians 11.25).

Only Matthew, (which I regard as the latest gospel and not altogether reliable), includes the phrase “for the forgiveness of sins.” (Matthew26.28); the writer may have added it as a pastoral response for his church.

So Jesus said simply something like, “This is the covenant in my blood”.

WHY SACRIFICE?

If the background of Jesus’ words was the Temple sacrifices, what sort of sacrifice did Jesus have in mind?

Forty years ago I read a short book ‘Sacrifice and the Death of Christ’ by the wonderful Methodist theologian Frances Young, (£2.39 from Amazon). Here is a summary.

In the ancient world, worship and sacrifice were virtually synonymous. Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher and a contemporary of Jesus, discussed sacrifice in terms of three categories: communion sacrifices, whole burnt offerings (where we get the word holocaust from), and sin-offerings.

- Communion-sacrifices (Leviticus 3 & 7) were an expression of fellowship, a communal feast with God as the host. Any eating of meat was a cause of celebration and it was natural to offer it first to God, as in the practice of Jewish kosher and Muslim halal practices. This sacrificing of animals to celebrate together became less important after Jewish sacrificial worship was centralised in the Temple at Jerusalem.

- Whole burnt-offerings (Leviticus 1) were sacrifices of praise and thanksgiving, in which the whole animal was dedicated to God. After the exile the daily burnt-offerings in the Temple were seen as a continual act of praise to God.

- Sin-offerings (Leviticus 4 – 7) cleansed the offerer from any ritual defilement caused by unintentional breaking of any of God’s regulations. They did not cover intentional sinning.

THE BLOOD OF THE COVENANT

None of the above fits easily into Jesus’ use of the word ‘covenant’. The only part of the Bible where covenant is explicitly linked with sacrifice is in Exodus 24. It comes immediately after God has given the Ten Commandments, (followed by three chapters of detailed social and religious regulations). What happened next comes in Exodus 24.4-9:

Moses came and told the people all the words of the Lord and all the ordinances; and all the people answered with one voice, and said, “All the words which the Lord has spoken we will do.” And Moses wrote all the words of the Lord. And he rose early in the morning, and built an altar at the foot of the mountain, and twelve pillars, according to the twelve tribes of Israel. And he sent young men of the people of Israel, who offered burnt offerings and sacrificed peace offerings of oxen to the Lord. And Moses took half of the blood and put it in basins, and half of the blood he threw against the altar. Then he took the book of the covenant, and read it in the hearing of the people; and they said, “All that the Lord has spoken we will do, and we will be obedient.” And Moses took the blood and threw it upon the people, and said, “Behold the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you in accordance with all these words.” (Revised Standard Version)

This is the act which constituted the Hebrews as God’s covenant people. It seems to me that this was the background behind Jesus’ weighty words. His death was to be a sacrifice which would create afresh God’s covenant people, a covenant foretold by the prophet Jeremiah:

This is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. And no longer shall each man teach his neighbour and each his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” (Jeremiah 31.33-34)

If this is right, Jesus did not view his death as a means to take away sin or as taking on the punishment for sin. As the apostles reflected on the meaning of Jesus’ death and as they encountered the challenge of believing Gentiles, they introduced a whole variety of ideas about redemption and sacrifice and reconciliation. I quote some instances at the start of this article. But the words Jesus used at the Last Supper indicate that he saw his death as a covenant sacrifice, bringing into God’s (new) community all who remembered Jesus’ death as God’s obedient servant.

So every time we take the bread and wine of communion, we can hear Jesus saying to us ‘Welcome to God’s people’. That is pretty strengthening and consoling. If the problem of sin is the gap between us and God, then Jesus’ welcoming us into the covenant people of God is the solution. That is good news!